Karashi-zuke

At times we seek a heat that’s not spicy. The slow building warmth of ginger. The clear-cut through your sinuses of wasabi. Eyes tearing up from that hit of hot mustard.

Hot Mustard. Oriental Mustard. Asian Mustard. From the ground down seeds of Brassica juncea. When was the first time I tasted it? Oddly I think it was as a child in Provo Utah, in the back seat of the yellow VW Rabbit, a twenty piece McNugget on my lap. Later in Chicago on the sidewalk, sitting on my board and squeezing a tube of it onto my egg roll. It can seize your head. Ring a clear bell through your ear tubes. Fill your mouth with a flash of heat then vanish. Flash after flash. Not pain so much as alarm. This is karashi.

Karashi-zuke. Vegetables fermented in a mixture of sakekasu and mustard. The recipe most often sited is for nasu. Eggplant, with myoga or ginger, this is called nasu karishizuke or karashi-nasu.

For my first go at it I used a mustard that we had made with yellow mustard seed and brine from a green tomato chutney. It was head removing in its potency. We put it into the cave and forgot about it for two years. When we stumbled upon it again it had mellowed substantially but still packed a wallop. I mixed the mustard with whole baby eggplant and myoga and fermented it in an 18 month burdock kasu.

In just eight weeks the pickle was astonishingly good. The eggplant wasn’t quite ready throughout the ferment- though some were choice most had not fermented through yet, with tough skins and Styrofoamy flesh. The myoga, however, was fantastic. The shoot had become nearly translucent and the piquancy of myoga and mustard went one for one in a tremendous balance of suddenness and intensity…. and dissipation. As this pickle aged and the eggplant fermented through it became truly special. The myoga remained the star.

The following spring I used the, at that time nine months old, karashi-nasu kasu to ferment straight myoga for a dinner at Elements in Princeton New Jersey. In the dish Chef Mike Ryan combined nukazuke celery root, fermented in the nukadoko I had made for them, re-hydrated dried celery root, a dice of clam and its’ abductor with a muscle aioli, and karashizuke myoga- all in a broth of roasted tomatillos, clam innards, woodruff leaves and flowers- then garnished with foraged wisteria flowers. Beautiful and delicious. A wonderful dish.

This year we took a different approach. We made a mustard of brown and yellow mustard seed that we hydrated in jalapeno kasuzuke liquid. When we ferment a vegetable with a high water content, like say a pepper, in sakekasu it usually develops a layer of liquid that is something like a syrup of pepper juice and kasu. I try to siphon this liquid off so that it doesn’t thin out the sakekasu too much at the time of packaging. I save the liquid as a fermenting medium. We aged the mustard for a couple of months. Though it had its merits, I didn’t enjoy it like the previous mustard. It lacked the potency that I think of as karashi. I also used Japanese eggplant which I cut on the bias at about 5mm, and used ginger instead of myoga. Perhaps most importantly we used virgin kasu from Takara rather then our house fermented kasu.

The results were completely different. In two months time the eggplant was pleasantly fermented through. Though not quite melt in your mouth it did have a sort of yielding toothsomeness, just shy of luxurious. The ginger was bright and hot. The mustard, unfortunately, was all but lost. It was far too subtle for my taste, and for what I was hoping for. The kasu had the same salt and sugar percentage as the original version but was much younger. The sweetness had not metabolized out and the salt was still rough and forward, though not unpleasantly so. The staff loves it. It’s eggplant candy. A success within a failure- the best kind.

-Kevin

Shibazuke

Eggplant has proven itself a challenging vegetable for us to pickle. We have been disappointed with the color as it often turns a corpse like blue-grey, and with the texture, which has been either styrofoam or mush. However it had been a number of years since our last attempt and I really wanted to add a new pickle to the tsukemono line. I had my eye set on shibazuke.

Shibazuke is a traditional lacto ferment of eggplant, shiso, & ginger. The pickle is said to have originated in Kyoto, Japan with some recipes calling for the addition of cucumber and myoga (the new shoots of a ginger relative). While looking for recipes I had trouble finding one that was fermented, most calling for acidification by means of rice vinegar or umezu (the brine from umeboshi). I reached out to Naoko Moore, a culinary educator in Los Angeles, who has the informative website naokomoore.com and is co-authoring, along with Kyle Connaughton, an up and coming book on Donabe (claypot) Cookery. Naoko sent me a very authentic and basic recipe for Shibazuke.

The technique is a bit of a departure for us. Usually we will cut or shred our vegetables, salt them at about 2%, let them sweat for the day, and pack them into the vessel, the brine covering the top, allowing them to ferment for an average of six weeks or so. In this case we layered the eggplant, shiso, and ginger- salted at 5%- and allowed the brine to develop in the vessel under weight. We fermented the pickle for only 2 weeks.

The resulting pickle was truly wonderful. Salt forward, the eggplant had great texture with a acute ginger bite. But this pickle is really all about the shiso, it’s herbal pepperiness weaves itself throughout, and that color. That Color!!

Smoked Salmon Ibushi-Gin, Charred Kyoto Eggplant, Sesame Miso, Gingko Nut, Shibazuke

Photo & Dish by Kyle Connaughton

Soon after leaving the fermenting vessel the shibazuke was jarred up and left the Shop, headed for Chicago, where it sat next to donabe smoked salmon in a dish created by Chef Kyle Connaughton for this years Imbibe and Inspire conference.

The eggplant texture reminded me of the flesh of the Royal Trumpet mushroom, which I was scheduled to receive a few pounds of the following week. I was eager to apply the technique to the fungus.

If possible I enjoyed this pickle even more. The subtle earthiness of the mushroom was still present and the texture has reminded many who have tried it of tender squid or octopus. Delightful!

-Kevin

Sakura No Shiozuke

A beautiful Sunday morning in May. The blossoms arrived in a woven basket hanging off the arm of Jeffrey Stoneberger who arrived at The Shop with his usually flurry of activity. Out of the basket the blossoms swayed on branches, ethereal and cloud like, in a shifting range of pink to white, petals drifting down to the table top.

What to do with them? Kombucha for sure.

What else? How does one capture the delicate in its profound and fleeting moment?

The Japanese have a tradition of preserving cherry blossoms in salt. Sakura no shiozuke.

The technique is a bit of a departure for us. At the shop we create acids. This called for adding one: vinegar. As it happened, Jeffrey also brought with him an exquisite pear-sake vinegar that he had crafted with all the love and care that characterizes his work. The project seemed fated.

The next morning, while plucking blossoms for an infusion we would ferment with a kombucha SCOBY, I put aside many of the tight pink buds and the vibrant and sturdy newly opened blossoms. I salted and pressed them for three days. Such an incongruous treatment of these delicate structures. On the third day, I drained off the modicum of brine that had developed and mixed the blossoms with a small amount of the pear-sake vinegar. They sat in the fridge for a week. I then laid them out to dry on a rack for a day.

A moment of textural give. A hint of spring. Floral then gone. A touch of acid on the tongue.

The salinity lingers.

I repacked them in salt for the future.

Two weeks later I was bottling cherry blossom kombucha. I carefully placed the blossoms, that had fermented in the kombucha, into the bottles with chopsticks. Across from me sat two of my favorite people to come into The Shop, Kyle and Katina Connaughton, who had come in for a visit and were doing a tasting of our tsukemono. Kyle was scheduled to cook at a benefit in New York for the Edible School Yard. He would be cooking with a number of other notable chefs in an effort to raise money so that the city’s children may have a garden in their schools that they could sow and reap from during some pretty formative years. Establishing connection. Eighteen years ago, when Alice Waters launched the Edible School Yard Project, the flagship garden was to be located at King Middle School in Berkeley. We had just left the farm and were living with Alex’s parents. We had no jobs and our son Keiran was 4 months in utero. Both Alex and I applied for the position of project manager for the fledgling garden. Neither one of us got an interview. Needless to say it has grown way beyond any scope and vision I may have had as a scared and unsettled twenty-five year old. All for the best, as it turns out we had other things to do. Kyle wanted to bring some tsukemono to New York with him. He asked if I had any sakura no shiozuke to give up. I did, and the following week he used them to garnish a sashimi dish, on the other side of the country, for a very worthy cause.

This here is the sweet spot. To make a tiny gesture to preserve a moment in time, all that made it possible and all its possibilities.

300 grams Cherry Blossoms

3 tbsp salt

3 tbsp vinegar

-Kevin

Summer Cucurbit Winter Cucurbit

It is this time of year that we finally become a pickle shop. Without fail, folks will wander into The Shop from January through June, stare blankly at the retail cooler for several minutes, then look up at us and ask, “Do you have any pickles?” For the first few years, it was all we could do to keep from bursting out laughing. They were, of course, looking at a cooler full of pickles. But we know, as you surely know, that they are looking for cucumbers. Cucumis sativus or perhaps Cucumis anguria. From the family Cucurbitaceae. Squash, melons, and gourds.

By far the most fermented cucurbit in the United States is the cucumber. Fermented in a salt water brine, usually with dill and garlic and a variety of spices, it’s ubiquitous. The pickled cucumber came to this country with immigrants hailing from Northern Europe through its far Eastern reaches. They are known as Pickles. They are Pickles.

Besides cucumbers, we see a variety of melons and gourds fermented throughout Asia. What we don’t tend to see is Winter Squash. Cucurbita Maxima (think buttercups, kabochas, hubbards) and Curcurbita Moschata (think butternuts, and peachy skinned pumpkins). They challenge one of The Shop’s basic rules of thumb: is this vegetable pleasant to eat raw? Winter squashes challenge this rule with total grace. They are by their very nature storage vegetables. Crazy hard shell. Dense flesh. Winter sustenance. So why bother? In our mind’s eye when we think of these sugar powerhouses it is of familiar comfort foods—pumpkin pie, butternut squash soup, a kabocha puree. They can be some pretty serious, stick to your ribs, sweet mush. We say that with complete respect, this sweet mush is amazing, and along with scarves and the sound of rain on skylights, it might be our favorite winter reality. And maybe because they are some of our favorite foods, we are drawn to explore them deeper. Often people think that Winter Squash tastes like pumpkin pie mix. What if we take away the cinnamon and the caramelized creaminess and tried to approach them from a different angle? With texture. Cooked, but not. Crunch without the back of your throat starchiness. A whole palette of amber, umber, ochre. Preservation not borne of necessity but of pure curiosity. Luxury.

Pumpkin, Espelette, Scallion

Made with a Musquee de Provence Pumpkin. When you crack them open they look like giant papayas. Do not attempt with your common jack-o-lantern, they are far too dry and flavorless. A crunchy and juicy 2mm julienne works well. They are not at all fibrous. Brine the color and body of orange juice. The scallions for color and crunch. The Espelettes add a well balanced warmth.

Fairytale pumpkin. Enormous pleated flesh colored things that decorate the front of our shop all winter. We set the 1/4-inch thick slices into our favorite barley miso in January 2012. At this point, some eighteen months later, they are great. Part pumpkin, part miso with a fabulous texture.

Again we used the fairytale here. We adore this pickle. The color has remained rich and vibrant. Though thoroughly fermented, there is still a textural snap and crunch that gives you the raw experience. The floral components of the koji and the booziness of sake pair so well with the natural sweetness of the pumpkin.

Standard and reliable. The squash will retain its texture better if each piece is cut with a bit of the rind side intact. This kimchi is one of our perennial fall favorites. We have paired the butternut with various mushrooms and even huitlacoche, always with great results. Note: Shiitakes will often cause accelerated textural breakdown in ferments, so be prepared for things to be a bit softer if you choose to work with them.

Totally seductive, effervescent butterscotch. Pumpkin-Rooibos Kombucha is a warm caramel union of rich, earthy, red Rooibos tea and deep golden Fairytale pumpkin. We join the bright southern light of the high desert of South Africa with the autumnal glow of Northern California.1 It’s a delicious beverage.

We’ll venture to say that the exploration of winter squashes has been and is one of the most gratifying projects of the shop. Beautiful. Mind-Expansive. Conversation-Forwarding. Unexpected.

-Kevin & Alex

1-Victoria K Fort

What Do Cherry Blossoms Do?

Recently, on a Saturday morning, as I was finishing setting up the stand at the Berkeley Farmers Market, a customer asked me an extremely complex question. The early shoppers tend to be our most regular ones—eager to get first pick at whatever new concoction we might have—and indeed this shopper is what I would consider a great customer. I see her most every week and she purchases an average of 3-4 items: almost always a Nutra Kraut (our super blue-green algae kraut), a seasonal kimchi for her partner (she doesn’t do spicy), and usually a Kombucha, most often something with ginger or turmeric. She returns her bottles—although definitely not cleaned—and is generally pleasant.

So, as she’s perusing her options on the Kombucha stand (generally first thing in the morning I have about 10 options) she asks in the same tone as she might inquire what time it is, “What do cherry blossoms do?” Cherry Blossom Kombucha was an option that morning. It had never been an option previously and wouldn’t again for quite some time. And even then, chances are it wouldn’t be as perfect as those two dozen bottle I had with me that morning.

I am presented with an interesting challenge when someone asks a question that I process as ludicrous. Yes, I knew she wanted a direct response as to the precise positive action cherry blossoms would perform within her body: some particular nutrient or enzyme they were particularly well endowed with, some reason why this $6 investment would be sensible. But damn, I was so unable to answer. If I could provide the answer she was searching for, even speak in the same language for a few moments, I could be released from the awkward exchange sooner. But I can’t do it; it is the wrong question. Not only does it not make sense, I think the sentiment behind it is flawed. “What do they do?” I responded right back at her, “They’re cherry blossoms.”

“No, you know, like what are they good for?” she clarified, slightly annoyed that we seemed not to be communicating. “You know…like turmeric is good for inflammation….”

Yes, I am a true believer in the food-as-medicine lifestyle. Yes, particular foods are particularly healing for specific conditions. I have dedicated my entire adult life to the study of nourishment. But I believe the inability to view the whole as more than the sum of its parts has become a pathological condition for many in this community, and it is not making anyone healthier.

One weekend this May, we were fortunate enough to receive an outrageous amount of luscious, pink, fragrant cherry blossoms. The next morning we made a concentrated infusion, and introduced—quite possibly the first date for them—a Kombucha SCOBY. Over the next couple weeks, the petals intertwined themselves within that zoogleal mat, gurgling happily, creating in their union what I would describe as the most perfect of fairy garments. At bottling, this brew was mixed with some raw local honey and the bottles, each one with cherry petals chopsticked in, sat in our cave over two more weeks.

You really never know until you open the bottle. You could have done everything to this point “right” and still it could really suck. But from the smell you know. And the smell of the cherry blossom kombucha, bubbles dancing under the nose, encouraged some pretty large smiles. Indeed, sometimes the smell can hold such subtle beauty that you feel like you are being let in on the most fantastic of secrets. The delicate dance of the blossoms as they floated to the surface after the top was released was pure joy and delight to behold. The fairytale dress SCOBY had produced a fairytale flower champagne.

What do cherry blossoms do? I’ve thought about that question a lot over the last couple of months. Nothing and everything. I believe that resonance holds more power than any specific index of values ever will. Story and alchemy surround you. Pay deep attention to your food and it will feed you deeply.

-Alex

Dessert

Tsukemono Sundae

Kasu Ice Cream & Umeshu Ice Cream

Shiro Misozuke Banana

Koji Fermented Adzuki Bean “Hot Fudge”

Nuka Cultured Whipped Cream

Umeshu Cherry

There is a word that all of us who make food for people use everyday, when we set plates on tables or slip jars into hands. Enjoy.

Enjoy.

A conjuring of intent. A prayer. A desire, perhaps, that the work we’ve created will be appreciated. Deeply.

Our work is understood to be healthy. By that I mean that there are measurable health benefits to consuming our products. Mainly this comes in the form of bacteria. They keep our engine running. They are our engine running.

We fully embraced this from the beginning. The words probiotic bacteria can be found on our label along with Restore & Revitalize and an FDA disclaimer. We know. We understand. People want, people need. We deliver.

I don’t think much about the health benefits anymore. Not in any direct or overt way. They are, for certain, a thread that weaves through all of our work. In so much as they spring from that which provides the very action of the work, their importance cannot be overstated. It is foundational. A given.

What we seek is creative collaboration with these fundamental forces, to give rise to something delicious.

Occasionally when we are reminded, we are caught a little off guard, left a little speechless. Example: At the farmers market a while back, Alex slid a jar of sauerkraut into the hands of a customer and said pleasantly, “Enjoy,” to which he gruffly replied, “I don’t eat this because I enjoy it, I eat it because it’s good for me. It’s not ice cream.”

Well, he does have a point there. Pickles are not ice cream.

-Kevin

June Garlic

It’s all about the timing. The garlic has to be fresh dug. Cloved but not cured. The skins are thick and need to be cut away with a paring knife to get to the tender kernel. From late May through early June we dedicate a lot of time at The Shop to Garlic. The young tender cloves will be buried in our favorite two-year barley miso and left to age, in the jar they will be sold in, for one year in the cave. People often ask me what my favorite product is that we make. I always dismiss this question with the usual, “What? Please! You are asking me to choose amongst my children.” But this—June garlic fermented one year in barley miso—this is it. My favorite child.

Over the year the garlic ferments through. Umami rich, they are salty and sweet and pure garlic without the heat and volatiles. I can pop them like candy. They age beautifully. We have vintages going back to 2009 and the depth of flavor seems endless. But the miso itself is the reward for the patient. Garlic has permeated; so much so that you’d be hard pressed to cook this flavor into miso. Delicious.

-Kevin

Home Production: 1996-99

It’s been a haul. In the beginning, we set up shop in our small ground floor apartment. There were years of nights spent up so late. So many nights when the baby wouldn’t go down, or stay down, and at two or three or more in the morning under the harsh light of florescence we’d be in our kitchen, with the babe in the backpack snoozing—or more likely not—and there would still be so much more clean up ahead and I would have to leave in a couple of hours to shelve catalog items for retail consumption at a Smith & Hawken garden store. I agree that normally we aren’t able to recall painful moments in too clear of detail as to save us from the trauma of having to relive the episode. Though I have to say, I remember the kitchen so well. The cupboards were this plaid of gray, red, and orange blocks with thin yellow stripes. The linoleum tiles of the kitchen floor were Etch-A-Sketch gray from centuries of traffic buildup. The kitchen was about 90 square feet. It housed the cabinets mentioned above, that only extended far enough along one wall to offer a single basin stainless sink. A sink which, it should be said, was placed into a countertop of yellow and brown leopard print Formica. It also contained a mustard-colored stove with a matching hood, of course. The refrigerator was white and modern, but lacked a water and crushed ice dispenser. We had a small white table from Scandinavian Designs with a hinged leaf, should we be expecting company, and four wooden chairs with rattan seats. It was also partial home to a huge industrial-grade stainless steel reach-in refrigerator, the rest of which extended into the entryway and blocked the front door from opening entirely. A 4′ x 2′ stainless steel Metro shelving unit sat in front of the kitchen’s only window and supported, above the ground (in accordance with health codes floating in a sea of violations), five-gallon stoneware crocks filled with Brassicas in full ferment. There was another Metro shelf perched on the wall between the big fridge and a doorway. The doorway encompassed a step up to the living room which was floored with parquet and had a very, very low ceiling. The living room housed refrigerator number three. This one no longer functioned and was not plugged in. It was white and had a hole in its side where apparently a bullet had entered never to return. Under the bullet hole there were streaks of rust, looking like blood, running through the letters W S B which were rendered in fat blue marker ink in the style which everyone recognizes as the Gang Font. West Side Berkeley is an appropriately named outfit that contains some of the most ambitious taggers of all the local social clubs. Their initials are scribbled liberally across the town’s nooks and crannies. Inside the fridge I had rigged up an incubator switch to a light bulb which kept the compartment within the perfect 30-degree variance of 74 to 104 degrees. We used it to incubate white sushi rice which had been inoculated with the mold spores of Aspergillus oryzae, for koji, which we then set free in a vat of salted soybean mash to make miso. We used it to inoculate soybeans themselves with Bacillus subtilis natto or Rhizopus oligosporus for natto and tempeh respectively. Next to the gangsta fridge was a wooden warehouse pallet which was average in size and on the ground supporting vessels full of fermentation. On the other side was the koji table, where the koji was processed once incubation was complete. There was so much controlled rot occurring that, with the nearly palpable energy of transformation, there seemed to always be a buzz, felt above the hum of the fridges and the drone of the florescent bulbs above. Felt even above the buzz of insufficient stereophonic that Bob Edwards’ voice echoed out of, carried on the first broadcast out from D.C., earlier than most truck drivers would catch. We were mostly slumped over ourselves by this time in the evening. That is except, of course, for the sleepless young one. I wonder if the energy of the house, due to the alchemical atmosphere, caused the babe to be mostly awake unless in motion for the first two years of his life. Or perhaps it was us clanging around every night until the witching hour. So we would be there amongst all that in the kitchen and the boy would be on my back in the Tough Traveler pack. I recall feeling stunned, like in the headlights, with all of this around me. There I was sifting around in drifts of shredded cabbage on the linoleum, the light gleaming off the stainless all around, and it’s later then I can feel, and I’m madly wiping at the deposits of crushed Cruciferae in the crevice of the fold down leaf of the white table. And you know what? NPR can be so disconcerting at this time, feeling like this, with Bob Edwards saying, “Good morning—NATO has launched air-strikes in Kosovo—I’m Bob Edwards and this is Morning Edition,” and then the music comes up, and B.J. Leiderman gives us a rise and shine.

-Kevin

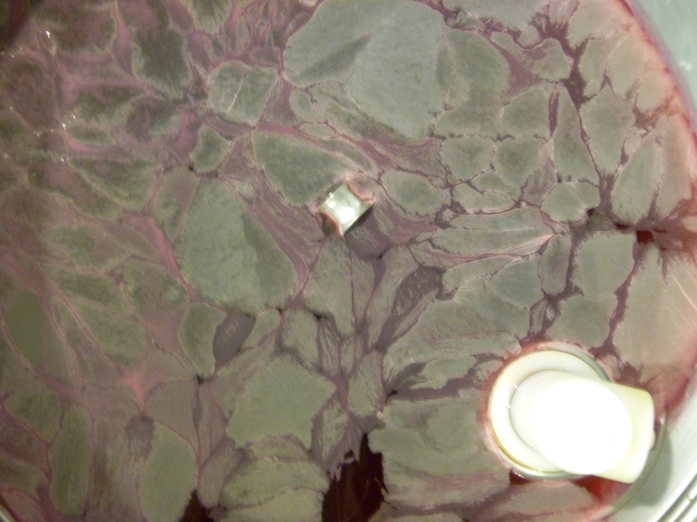

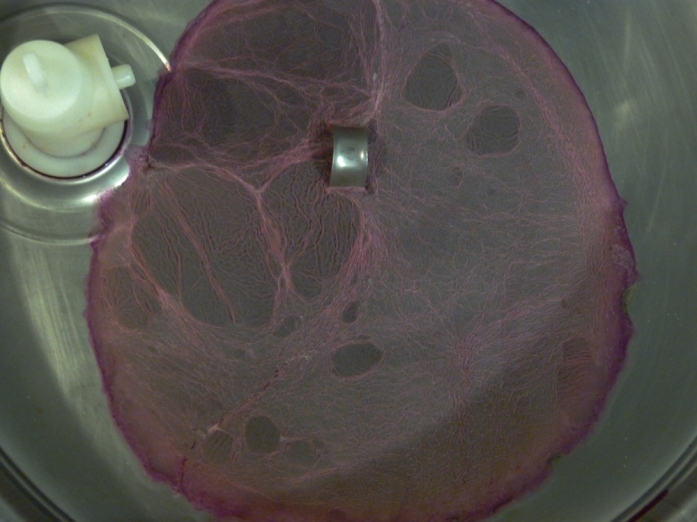

Everybody Kahm Down!

It’s not mold, it’s yeast, commonly called Kahm, which is a sort of catch-all term for a variety of yeasts that can form a film, or pellicle, on top of ferments.1 It’s harmless. No one is going to get hurt here. It’s alright, no need to panic. It’s incredibly common. It can, however, negatively affect taste. Our lid system prevents the yeast from coming in contact with the ferment. You can just scrape it off. Covering your ferment with cheesecloth makes it easier to remove.

1- In an early version of this post, I inadvertently named the yeast as Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Thanks to those who pointed it out and to Ben Wolfe for clarifying.

-Kevin